El pasado glorioso de la ciudad de Tombuctú

Tombuctú es una legendaria ciudad, siempre acompañada de historia y misterio, situada en el centro de Mali y muy cerca del río Níger. Es considerada una de las perlas del desierto del Sáhara y la ciudad de los 333 santos.

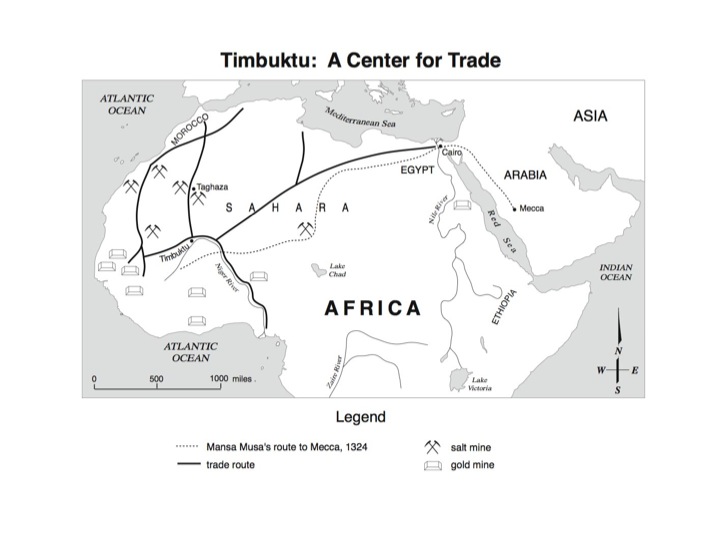

Parece, sin ser seguro, que la ciudad se fundó por las tribus de los tuareg hacia el año 1.100 d.C. Muy pronto se convirtió en un enclave principal de la zona del Sahel, y un punto de encuentro entre las caravanas de comerciantes tuareg que traían la sal desde el Mediterráneo y la intercambiaban por oro, fruta y pescado procedentes de las rutas del este y del sur. Tombuctú se convirtió así en una ciudad próspera.

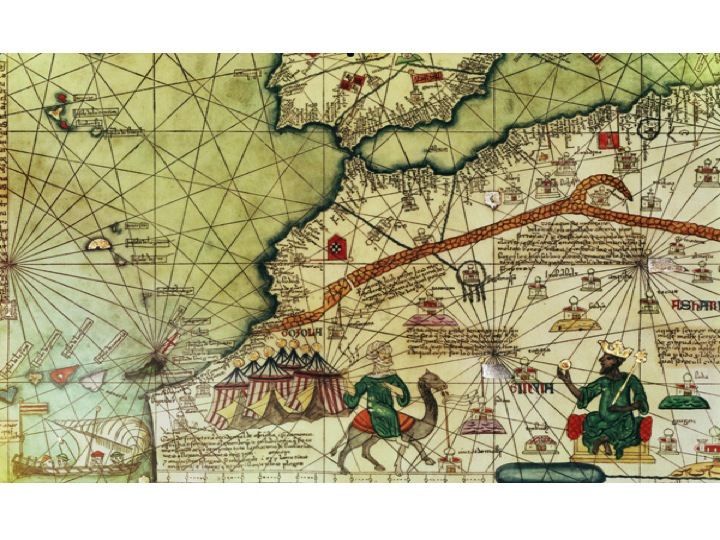

Su época dorada llegó un tiempo después, cuando el rey del Imperio de Mali Mansa Musa se anexionó la ciudad y favoreció la construcción de algunos de sus edificios más representativos. Mansa Musa (1280-1337?) era un devoto musulmán conocido por su peregrinación a La Meca desde la ciudad de Tombuctú. Se cuenta que movilizó más de 12.000 esclavos y que parte de su caravana la formaron 80 camellos que transportaban cada uno entre 30 y 120 kilos de oro. También se llevó Mansa Musa consigo a los hombres más poderosos de la ciudad, para evitar que durante su ausencia tuvieran ocasión de conspirar contra él.

Detalle de una página del Mapamundi de Abraham Cresques, de Mallorca. Mansa Musa aparece representado con corona y cetro al estilo europeo, y sostiene en una de sus manos una enorme pepita de oro.

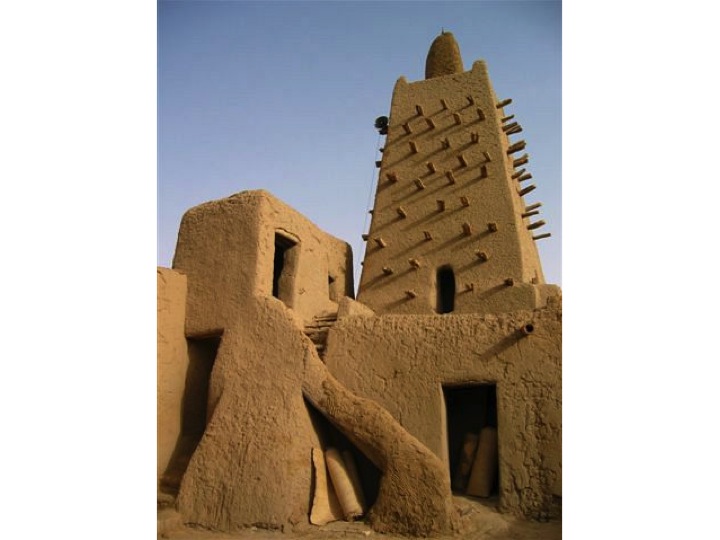

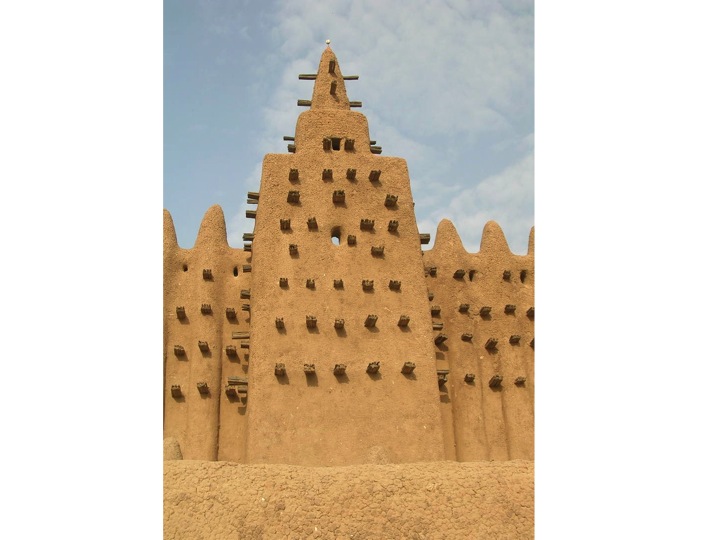

A su vuelta a Tombuctú encargó al arquitecto granadino Abu Haq Es Saheli la edificación de la Mezquita de Djingaeyber. Es Saheli había llegado hasta Tombuctú huyendo de una revuelta en el sur de Al-Andalus. El monarca le dio protección y trabajo. Es Saheli le correspondió con uno de los edificios más bellos de la ciudad.

La Mezquita de Sankore, después convertida en Universidad, fue también mandada construir por Mansa Musa. A ella comenzaron a llegar matemáticos, astrónomos y juristas musulmanes de otros lugares de África y Oriente Medio.

Tombuctú alcanzó su máximo esplendor durante los siglos XV y XVI, coincidiendo con la dinastía de los Askia y, tiempo después, con la anexión de la ciudad al Imperio Songhay. Durante el reinado de los Askia vivían en la ciudad más de 100.000 habitantes de distinta raza y procedencia.

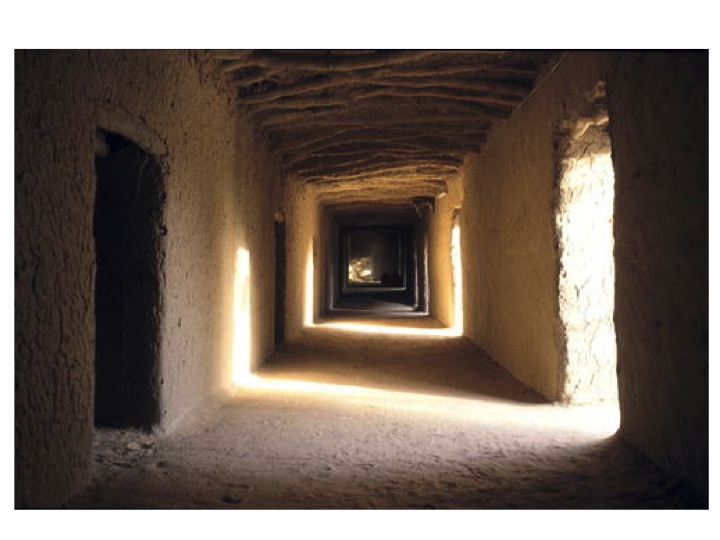

Por aquel entonces la ciudad tenía ya su conocida muralla y albergaba en el interior dos de las tres mezquitas y los edificios de adobe tan característicos de su arquitectura. Numerosas madrazas se instalaron también en la ciudad de Tombuctú. La ciudad comenzó a poblarse de pequeños santuarios dedicados a hombres santos que habían vivido en ella y protegían a sus habitantes contra el infortunio.

La ciudad seguía siendo un importante foco comercial.

Además, se había convertido en un referente cultural para Oriente y Occidente y una capital intelectual y espiritual a la altura de ciudades como Córdoba y Damasco. La citada Mezquita de Sankore es considerada como una de las primeras Universidades del mundo. A ella continuaron llegando estudiantes, letrados y científicos españoles, beréberes, mauritanos, árabes y persas.

A la ciudad de Tombuctú llegó también el morisco Ali Ben Ziyad al-Quti tras huir de la ciudad de Toledo en 1467. Se había llevado consigo su importante colección de manuscritos islámicos y medievales escritos en hebreo, castellano antiguo y árabe. Así comenzó la historia del Fondo Kati.

En cuanto a la dinastía Songhay, a un primer monarca con creencias animistas le siguió un nuevo devoto musulmán que favoreció el estudio de la religión islámica.

Hacia 1590, la ciudad fue invadida por los sultanes de Marruecos ayudados por nuevos moriscos que habían sido expulsados de Toledo y otras ciudades castellanas. El acceso a la ciudad se mantuvo prohibido para los no creyentes en el Islam, lo cual tuvo como justa correspondencia el extraordinario interés de los exploradores europeos de finales del siglo XVIII y del XIX para llegar hasta ella y sobre todo volver para contarlo.

Poco a poco la ciudad fue perdiendo el favor de los sultanes de Marruecos y su importancia decayó.

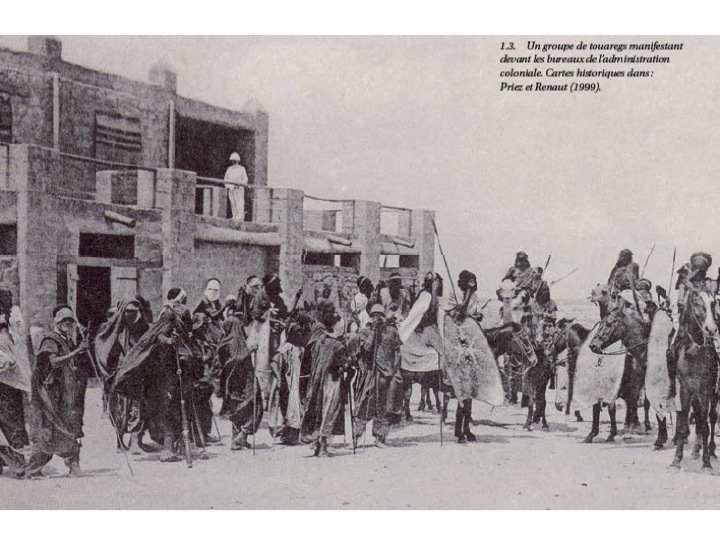

En 1893 la ciudad pasó a formar parte del Imperio Colonial Francés, tras haber opuesto las tribus tuaregs mucha resistencia.

Manifestación de un grupo de tuaregs ante la Oficina Colonial. Cartas Históricas, PRIEZ y RENAUT (1999),

En 1960 el Sudán francés obtuvo la independencia y comenzó a llamarse Mali. La capital se instaló en Bamako, en la mitad sur del país. Desde entonces las tribus tuaregs han reivindicado una mayor autonomía de la capital, o su total independencia, en al menos cuatro revueltas.

La última de las revueltas tuaregs se originó en enero de 2012. Por una serie de acontecimientos que se sucedieron en cadena tuvo como consecuencia la destrucción de una de las mezquitas de la ciudad, numerosos templos sagrados y antiguos manuscritos que se guardaban en colecciones privadas en el interior de sus murallas.

Sus templos sagrados

A principios de 2012 Tombuctú contaba con tres mezquitas y con al menos 16 templos dedicados a santos protectores de la ciudad.

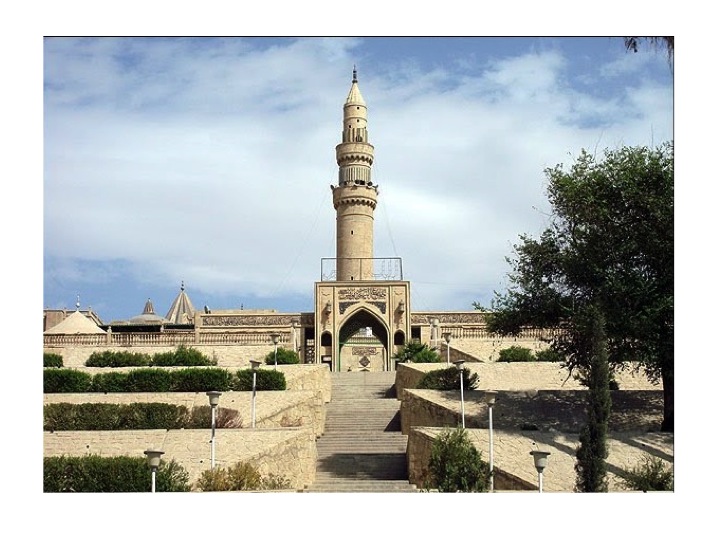

La Mezquita de Djingareyber

La Mezquita de Djingareyber está situada en el extremo oeste de la ciudad antigua. Como se ha señalado, fue construida por el arquitecto andalusí Abu Eshaq Es-Saheli al-Touwaidkin, por encargo del sultán de Mali Abu Musa a la vuelta de su peregrinación de La Meca en 1325. En una reconstrucción posterior, ya en tiempos del cadí de Tombuctú Elhadj Al-Aqib, se añadió su parte sur. La mayoría de la Mezquita está construida en adobe. Presenta tres naves interiores y dos minaretes.

La Mezquita de Sankoré

La Mezquita de Sankoré está construida en la zona noreste de la ciudad, en el barrio que lleva su mismo nombre. También mandada construir por Mansa Musa, entre 1578 y 1582 el Imán El Hadj Al Aqib la reconstruyó y otorgó las dimensiones de la Kaaba, que había conocido durante su peregrinaje a los lugares santos en 1581. Construida totalmente en adobe, su estructura y estilo es similar a la Mezquita de Djingareyber. Cuenta con tres naves y un minarete de unos 15 metros de altura. La parte norte alberga las aulas de la Universidad de Sankore

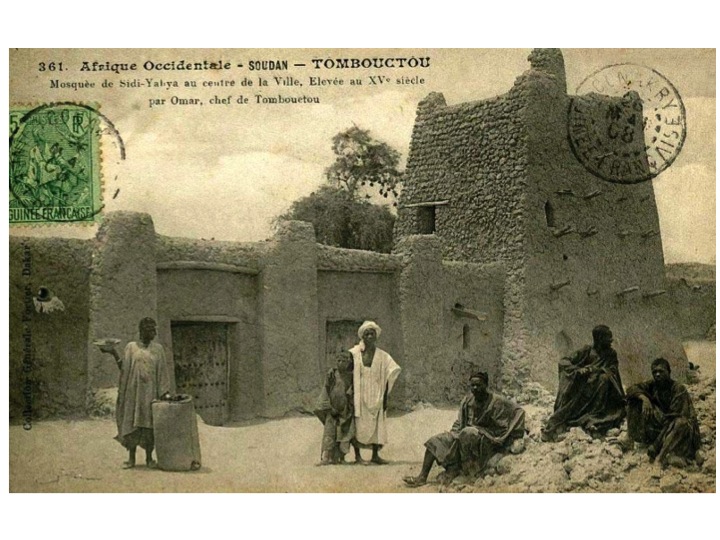

La Mezquita de Sidi Yaya

«Fortier 361 Timbuktu Sidi-Yabya Mosque» de Edmond Fortier (1862-1928) – Downloaded from http://www.dogon-lobi.ch/historical2.htm. Disponible bajo la licencia Dominio público vía Wikimedia Commons

La Mezquita de Sidi Yaya está situada en el centro de la ciudad antigua. Fue construida hacia el año 1400 por el gobernador Cheick El Mokhtar Hamallah, pero toma su nombre de un gobernador posterior, Sidi Yahia El Tadlissi, que reclamó las llaves de la mezquita unos años después. El santuario se restauró en 1577-78 y sufrió importantes transformaciones en 1939, entre ellas, el antiguo minarete se transformó en una torre y los arcos originales se sustituyeron por unos ogivales. La Mezquita comprende tres naves interiores para los rezos de invierno y un patio exterior para los rezos de verano.

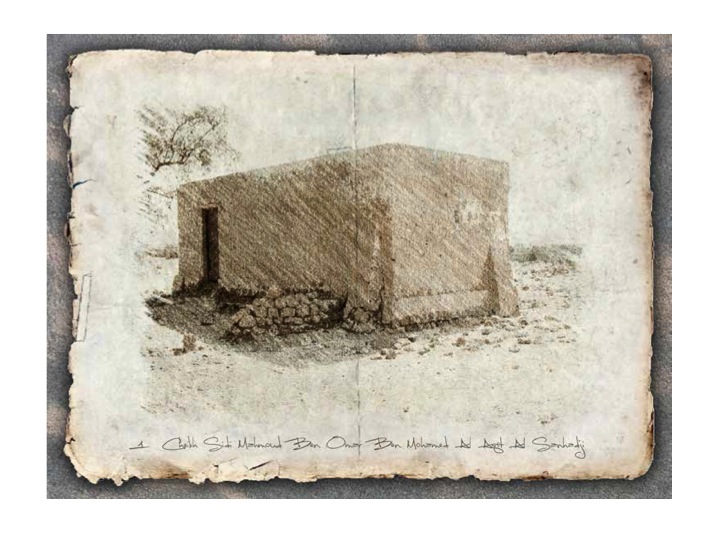

Por otro lado, los edificios destinados al culto de sus santones pueden parecernos no tan espectaculares como nuestras catedrales e iglesias románicas o góticas, pero para los habitantes de la ciudad tienen el mismo valor cultural y espiritual. En enero de 2012 existían 16 templos en Tombuctú. Los santos a los que estaban dedicados eran considerados los protectores de la ciudad y habían contribuido en tiempos remotos al progreso espiritual y filosófico de sus gentes. Sus nombres son los siguientes:

- Cheikh Sidi Mahmoud Ben Omar Mohamed Aquit

- Cheikh Al Aqib Ben Mahmoud Ben Omar Mohamed Aquit Ben Omar Ben Ali Ben Yahia

- Cheikh Sidi Admed Ben Amar Arragadi

- Cheikh Aboul Kassim Attawaty

- Cheikh Sidi Mohamed El Micky

- Cheikh Mohamed Tamba-Tamba

- Cheikh Al Imam Saïd

- Cheikh Al Iman Ismaïl

- Cheikh Sisi Mohamed Boukkou

- Cheikh Sidi El Wafi El Araouani

- Cheikh Mohamed Sankaré le Peulh

- Cheikh Sidi Mokhtar Ben Sidi Mohamed Ben Cheikh Al Kabir al Kounti

- Cheikh Alpha Moya

- Cheikh Mohamed Aqit

- Cheikh El Hadj Ahmed

- Cheikh Aboul Abbas Ahmed Baba Ben Ahmed Ben El hadji Ahmed Ben Omar Ben Mohamed Aqit

Nos ocupamos con un poco más de detalle del primero de ellos, siguiendo el informe del arquitecto urbanista Pietro M. Apollonj Ghett (vid infra, bibliografía).

Cheikh Sidi Mahmoud Ben Omar Mohamed Aquit (1494-1548) es un santo de gran reputación. Nació en Tombuctú en el año 868 de la Héjira y falleció en la misma ciudad el año 955 de la Héjira. Fue el primer santo venerado en la ciudad y se encuentra enterrado a unos 150 metros al norte de la ciudad, en su antigua casa, siguiendo la tradición oral. Junto a él están enterrados otros 167 santos. Era un gran erudito, profesor y jurista revestido de autoridad y dignidad. Fue además autor de numerosas obras. Padre de cuatro hijos, se dice que cuando falleció uno de ellos permaneció totalmente en silencio mientras recibía las condolencias. Unos días después se disculpó y explicó que había sido debido a que en aquel momento estaba siguiendo la lucha del alma de su hijo con los ángeles. El cementerio que rodea su santuario es el lugar de enterramiento de sus descendientes y de todos aquellos que le rinden culto a diario.

Cementerio de Sidi Mahmoud Ben Omar, con el Mausoleo de Cheikh Sidi Mahmoud Ben Omar Mohamed Aquit a la izquierda, y el Mausoleo de Cheikh Mohamed Mahmoud Al Arawani a la derecha, así como otras tumbas. c Pietro M. Apolloni Ghetti

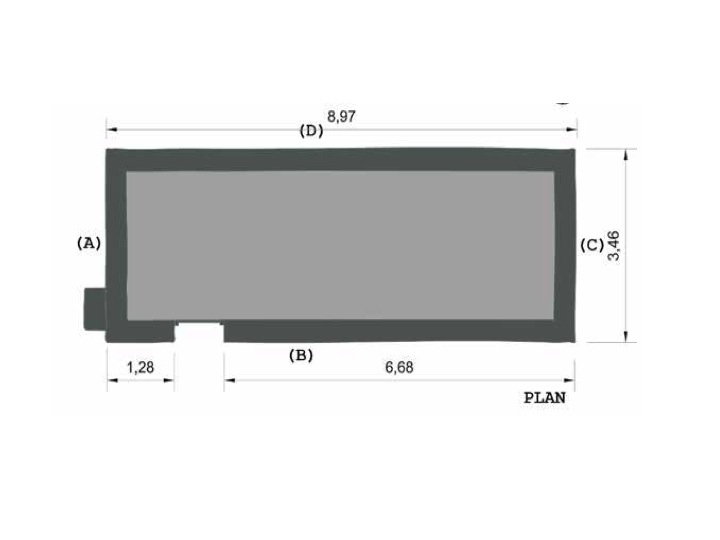

Esta es la planta del templo:

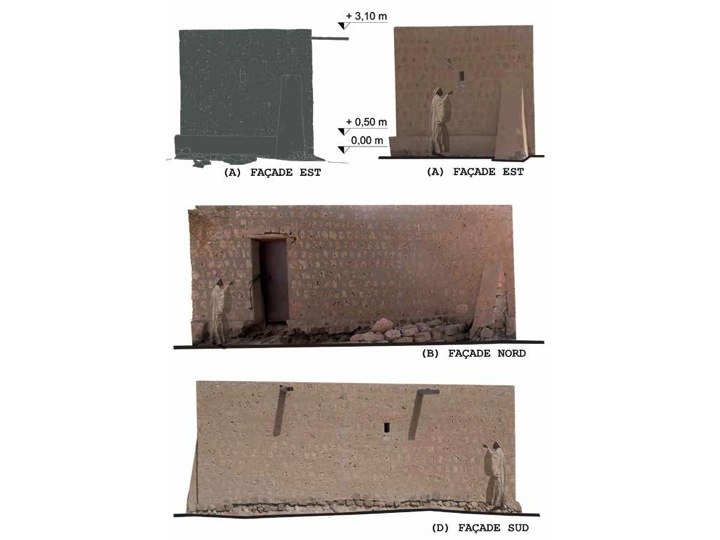

Aquí puede verse su alzado desde las distintas fachadas:

A raíz del conflicto, dos de las mezquitas y los 16 templos sagrados fueron destruidos por las milicias de Ansar Dine.

Así quedó el templo dedicado a Sidi Mahmoud Ben Omar Mohamed Aquit:

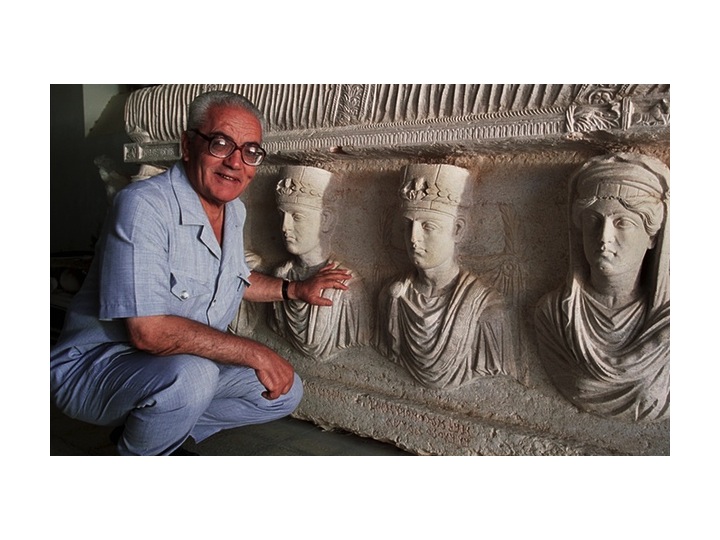

Sus antiguos manuscritos

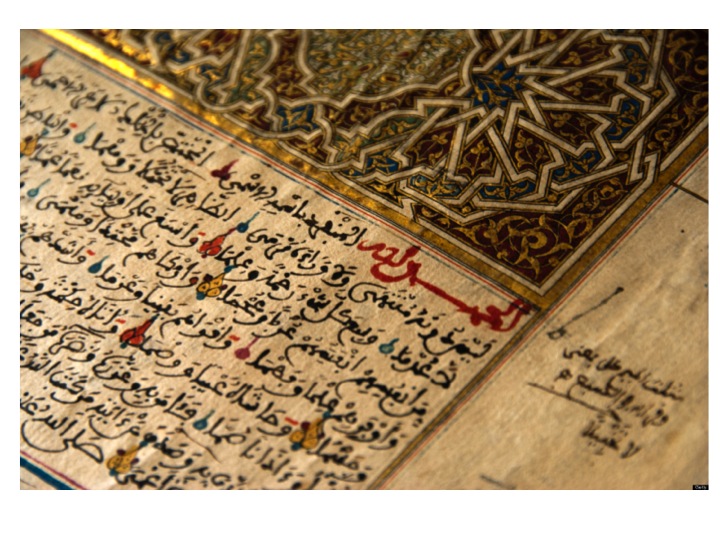

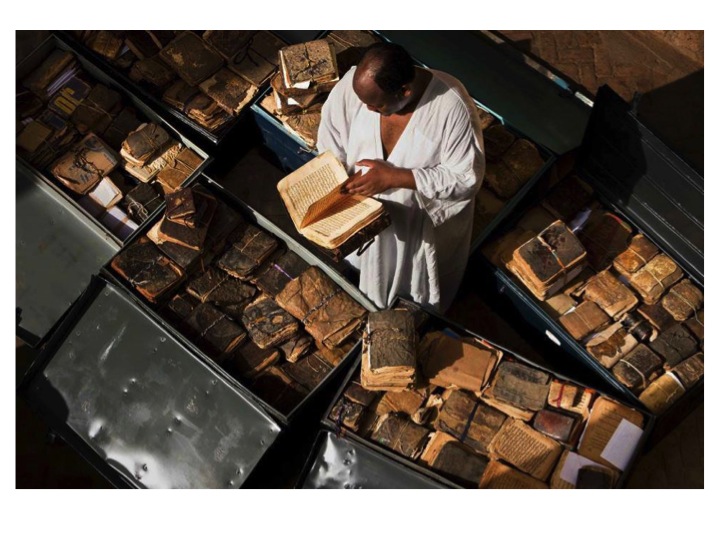

Tombuctú es igualmente conocida por las colecciones de manuscritos que han permanecido durante siglos en el interior de sus murallas. La mayoría de ellos llegaron a la ciudad en la época de su mayor esplendor y procedían de la península ibérica o del Lejano Oriente.

Ya nos hemos referido al Fondo Kati, que comenzó a gestarse a partir de un conjunto de documentos originales que salieron de la ciudad de Toledo junto al resto de pertenencias de Ali Ben Ziyad al-Quti cuando tuvo que salir huyendo de la ciudad.

Los estudiantes, pensadores, filósofos y escritores que se desplazaban hasta Tombuctú para aumentar su saber llevaron también consigo documentos originales que acrecentaron el patrimonio documental de la ciudad.

El conflicto de Mali surgido en enero de 2012 amenazó gravemente los valiosos manuscritos de Tombuctú. Muchos de ellos consiguieron salir de manera clandestina hacia otros países como España o hacia la capital. Así sucedió con el Fondo Kati.

Otros documentos no tuvieron la misma suerte. En Junio de 2013, tras una visita de evaluación, UNESCO estimaba que alrededor de unos 4.200 manuscritos del centro de investigaciones Ahmed Baba habían sido destruidos, y que otros 300.000 eran vulnerables al tráfico ilícito de bienes culturales.

Otros lugares sagrados de Mali

La Tumba de la Dinastía Askia en Gao

La Tumba de los Askia es en realidad un complejo que alberga varios edificios, incluida una pirámide funeraria de 17 metros de altura, dos edificios de techo plano que constituyen su mezquita, un cementerio y un ágora al aire libre. La pirámide funeraria fue construida por la Dinastía de los Askia en 1495 cuando Gao se convirtió en la capital del Imperio Songhai.

Las Ciudades Antiguas de Djenné

Djenné, cuyos primeros asentamientos se remontan al 250 a.C., fue un centro comercial importante y un eslabón de la ruta subsahariana del oro y la sal. A partir del siglo XV constituyó igualmente un centro relevante de propagación del Islam. Sus viviendas tradicionales, hechas de adobe y fieles a la arquitectura subsahariana occidental, se construyeron en pequeñas colinas para protegerlas de las inundaciones estacionales.

Los esfuerzos de UNESCO para recuperar el patrimonio cultural de Tombuctú

UNESCO siguió muy de cerca el conflicto que asolaba Mali desde principios de 2012, temerosa de que los enfrentamientos dañaran gravemente el valioso patrimonio cultural de Tombuctú y otras ciudades del norte, como efectivamente sucedió.

Tras varias visitas de evaluación, a principios de 2013 UNESCO comenzó a ayudar a las autoridades locales a elaborar inventarios sobre sus bienes patrimoniales, incluidos los dañados o difícilmente recuperables.

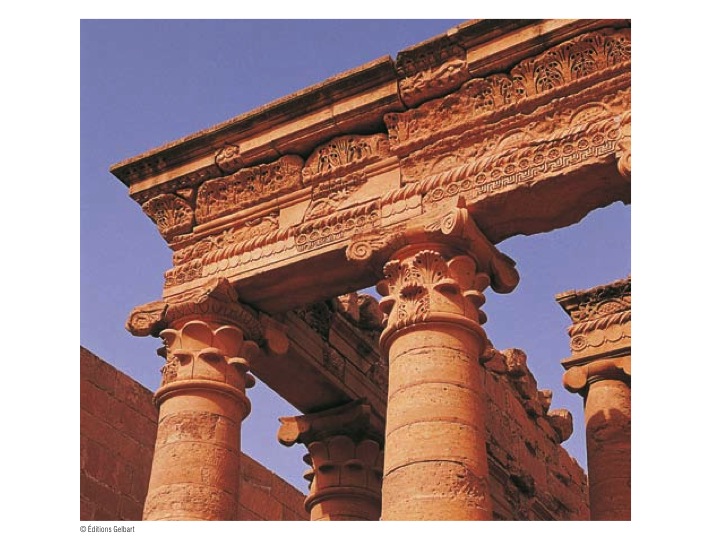

También centró sus esfuerzos en la implementación de un Plan de Acción que permitiera recuperar el patrimonio cultural dañado en Tombuctú, proteger sus antiguos manuscritos, y reforzarlas capacidades de conservación y gestión del patrimonio cultural de Tombuctú por las autoridades locales. El Plan de Acción se sitúa en la misma línea que otras iniciativas pasadas, como las que permitieron proteger los templos de Egipto durante la primavera árabe o reconstruir el puente de Mostar sobre el río Neretva. Con ellas se pretende devolver a las poblaciones locales elementos esenciales de su memoria y su indemnidad colectiva, así como contribuir a la reconstrucción de la paz y la reconciliación.

Como resultado de este Plan de Acción, en el verano de 2015 UNESCO anunció haber terminado con éxito la reconstrucción de las mezquitas y los templos demolidos por Ansar Dine.

La respuesta de la Corte Penal Internacional

La Corte Penal Internacional permaneció también atenta al desarrollo de los acontecimientos en Mali. Poco después de surgir el conflicto, advirtió a las partes contendientes que los delitos cometidos en el norte del país, incluido la destrucción de sus templos sagrados, podrían ser investigados y perseguidos por la Corte como crímenes de guerra.

En enero de 2013, la Oficina del Fiscal de la Corte Penal Internacional emitió un informe en el que concluía que concurrían indicios suficientes para abrir una investigación al amparo del Art. 53(1) del Estatuto de la Corte.

En Septiembre de 2015, a petición de la Fiscalía, la Sala de Cuestiones Preliminares emitió una orden de arresto internacional contra Ahmati Al Faqi Al Mahdi por la destrucción de los templos sagrados de Tombuctú.

Más información:

- Sobre los esfuerzos de UNESCO para recuperar el patrimonio cultural de Tombuctú, véase la página web Oficial de UNESCO sobre Acciones Urgentes en Mali

- Acerca de la respuesta de la Corte Penal Internacional, véase la página web Oficial de ICC sobre el Caso de la Fiscalía v. Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi y nuestra sección sobre Relevant cases

Bibliografía y documentos relevantes:

- APOLLONJ GHETTI, P.M: Etudes sur les mausolées de Tombouctou. UNESCO Publ., 2014, CLT.2014/WS/4.

- BERTAGNIN, M./ OULD SIDI, A.: Manuel pour la conservation de Tombouctou. UNESCO Publ., 2014. CLT.2014/WS/5.

- GUTIÉRREZ ZARZA, Ángeles: “La destrucción del patrimonio histórico como crimen de guerra: los Templos Sagrados de Tombuctú, Al Mahdi y la Corte Penal Internacional”, en Diario La Ley, nº 8664, Sección Doctrina, 14 Diciembre 2015, Ref. D-466, Editorial La Ley, p 1.

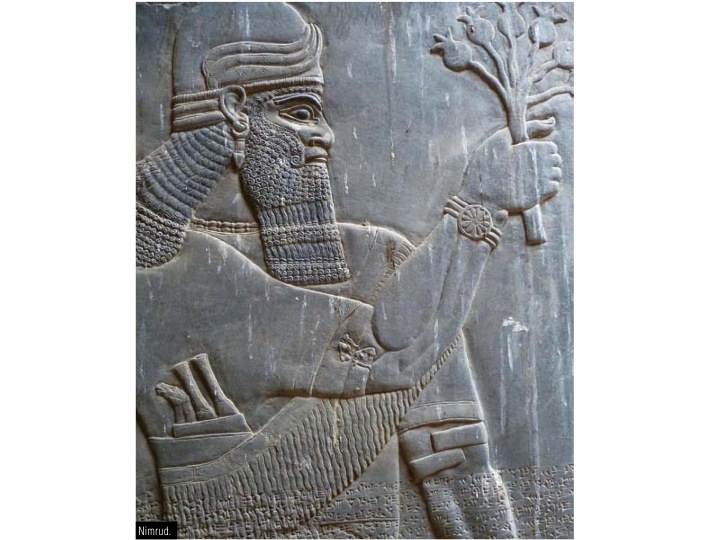

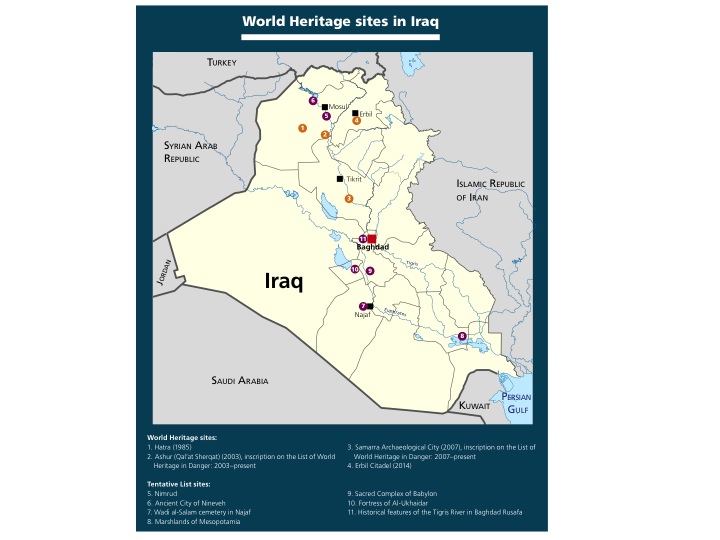

Information re Iraq is mostly extracted from:

Information re Iraq is mostly extracted from: